Bracing for Extreme Weather Events: How Climate Change Affects Future Hurricane Seasons

We are reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn affiliate commission.

With an official start date of June 1, experts predict another intense hurricane season in 2024 as the impending La Niña brings unusually chilly waters to the Pacific Ocean. However, more frequent extreme weather events are far from a phenomenon with worsening climate change.

How does climate change affect summer storms, and in what ways do these systems affect coastal communities? Here’s a closer look at today’s and tomorrow’s hurricane seasons and what the world can learn from past storms.

The Science Behind Intensifying Storms

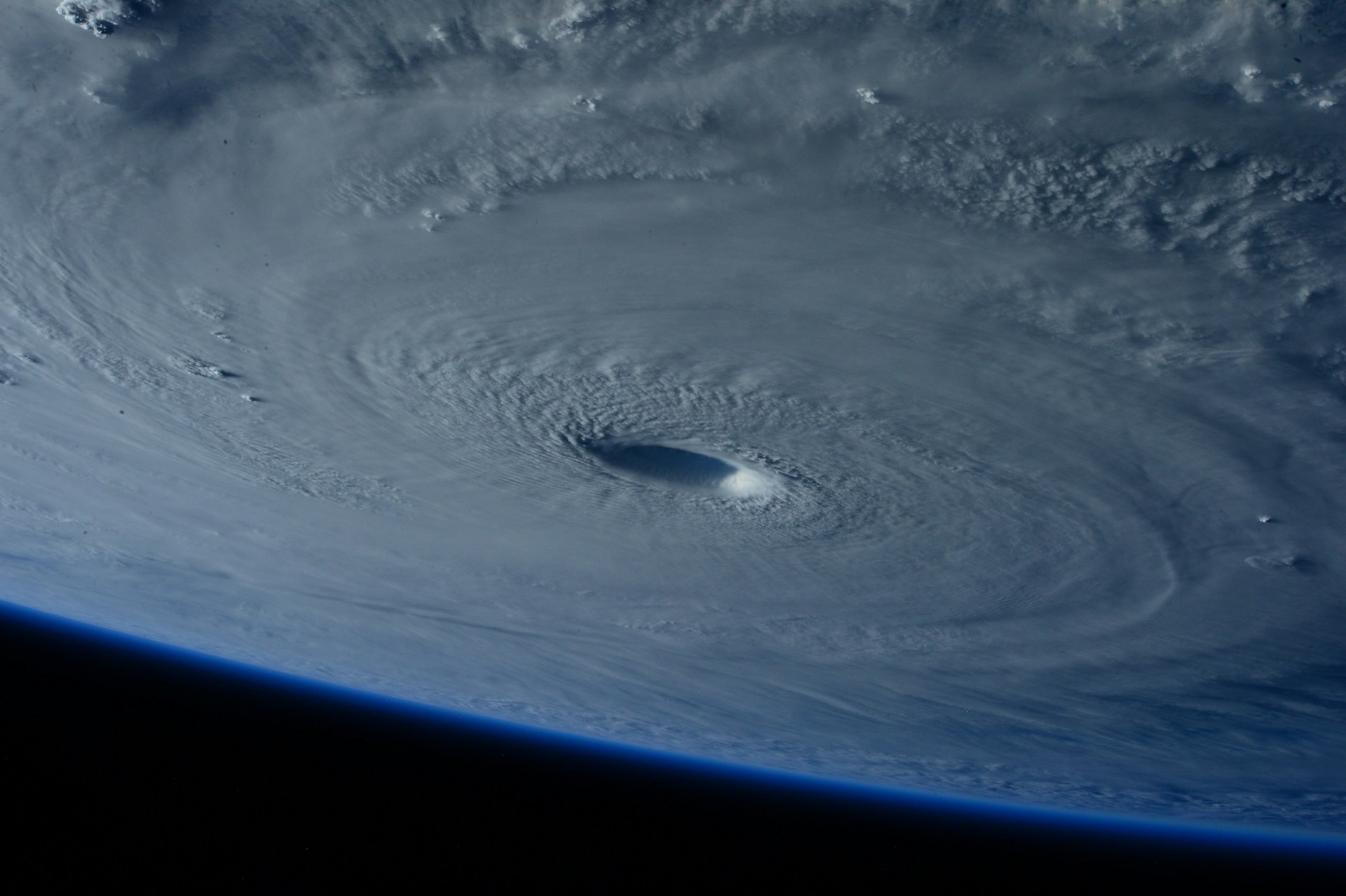

Worsening global warming means more extreme weather events worldwide — coastal regions are particularly susceptible to intensifying hurricane seasons. Generally, major hurricanes occur when excess water vapor evaporates into the atmosphere, fueling tropical cyclone activity.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, intensities will increase by 1%-10% as global temperatures rise by 2 degrees Celsius. Although it is challenging to predict storm size due to human activity, scientists expect Category 4 and 5 hurricanes to become more prevalent.

Major Hurricanes: The Impact of Extreme Weather Events

Severe hurricane seasons have devastating effects on the environment, economies and societies. Those living in coastal areas are at the greatest risk of infrastructural damage and weakened physical and mental health. Likewise, these extreme weather events create chemical and ecological hazards, inducing prolonged recovery, repair and expenditures. Here is how these worsening storms will continue leaving a mark.

Environmental

Post-hurricane damages are often shocking to see. However, many people don’t realize the extent of environmental fallout that heeds extreme weather. Major hurricanes negatively impact the environment in the following ways:

- Worsens coastal erosion

- Spreads environmental disease, affecting flora and fauna

- Decreases water quality by lowering salinity and oxygen levels in the ocean

- Hinders marine reproductive processes

- Produces harmful algal blooms

After 2017’s hurricanes Irma and Maria, 66% of coral reefs in St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands, declined within five months due to disease outbreaks. Yet, healthy reef sites are a barrier against waves, flooding and erosion along shorelines.

Meanwhile, in 2022, hurricanes Ian and Nicole in Southwest Florida pushed sewage and fertilizer through waterways, creating a blue-green cyanobacteria that was highly toxic to wildlife and the surrounding populations. Exposure could lead to the formation of another bacteria called Vibrio vulnificus, which sickens 80,000 Americans annually upon exposure.

Economic

Extreme weather events increased by 37% from 1990 to 2020, costing $1.8 trillion in damages. According to the White House, hurricanes and other storms costing over $1 billion have occurred at least once monthly within the last decade. This means the U.S. has rarely made it through a year without a billion-dollar storm for the past 10 years.

Extreme hurricanes disrupt business operations and daily life. Often, structural damages leave commercial spaces dark for extended periods, decreasing productivity until repairs are made. In the meantime, people remain out of work and unable to cover the essentials.

Of course, indirect costs must also be factored in before a hurricane hits, as people scour grocery stores and gas stations for food and fuel.

Social

Hurricanes can cause societal pains by damaging households, disrupting essential services, displacing people and straining crucial social networks. The aftermath could also lead to stress-induced trauma and other mental and physical ailments.

Hurricane Harvey — a Category 4 hurricane that made landfall in Texas and Louisiana in 2017 — flooded 30%-50% of properties that wouldn’t have been inundated without climate change impacts. Latino neighborhoods — especially low-income communities and those outside of FEMA’s 100-year floodplain — were hit the hardest, meaning they were ineligible for federal flood insurance.

As water contamination, air pollution and other environmental changes continue in the days and weeks after a hurricane, people’s health may decline. The stress of finding somewhere else to live — along with exposure to harmful toxins, injury and infectious diseases — makes communities more susceptible to illness and reduced psychological well-being.

According to one study, 11% of patients sought care for cardiovascular issues after Hurricane Katrina, 25% needed medical attention for their ears, noses and throats, and 17% experienced dermatological issues.

Of course, the worst fallout from major hurricanes is the death toll. While extreme weather experts do their best to give enough time to evacuate, not everyone heeds their call or gets the warning in time. In recent years, mortality rates have increased from intense hurricanes. Hurricane Katrina may have had the highest death toll at 1,833 when it hammered Louisiana in 2005, but 2017’s Hurricane Maria surpassed its count by killing 2,981 people.

Lessons Learned From Recent Storms

When Hurricane Maria battered Puerto Rico in October 2017, it decimated 400,000 homes — 55% of which did not meet building codes. Many low-income residents lived in these households, which were located in high-risk flood regions. The lesson learned: Build back stronger.

Resilience planning is crucial, such as rebuilding infrastructure to withstand intensifying storms. Adaptive management planning — setting metrics and goals to adapt to climate change — also helps communities better prepare and endure extreme weather events. For instance, after Louisiana lost 2,006 square acres of land following several major hurricanes, the Mid-Basin Sediment Diversion Program aimed to prevent future floods by reconnecting the wetland and the Mississippi River.

Additional lessons learned from recent major hurricanes include:

- Emphasizing evacuations: Evacuation orders are critical to relay to the public, giving them enough time to clear the danger zone.

- Enhancing communications: Effectively communicating the risks to the community during and after a major storm improves recovery and emergency response time.

- Mitigating inland flooding: Non-coastal regions may experience severe flooding, requiring swift action from emergency responders.

- Implementing natural buffers: Wetlands, barrier islands and dunes are crucial in slowing currents and decreasing flood damages. Coral reef restoration could also make a positive impact.

- Improving energy: Switching to renewables and upgrading electrical grids will keep the lights on during major storms.

- Banding together: Recovery from extreme weather events requires community members to work together to rebuild and assist others.

Extreme Hurricane Seasons Show Little Signs of Slowing

Without adequately addressing climate change, hurricane seasons will intensify. As a result, coastal communities must contend with the weather’s effects on the local environments, economies, and society. Of course, making drastic improvements to offset the climate crisis and implementing resilience planning can make a difference and protect populations at large.

Share on

Like what you read? Join other Environment.co readers!

Get the latest updates on our planet by subscribing to the Environment.co newsletter!

About the author

Steve Russell

Steve is the Managing Editor of Environment.co and regularly contributes articles related to wildlife, biodiversity, and recycling. His passions include wildlife photography and bird watching.